An interview with ‘Don’t Be Nice’s’ Nikhil Melnechuk

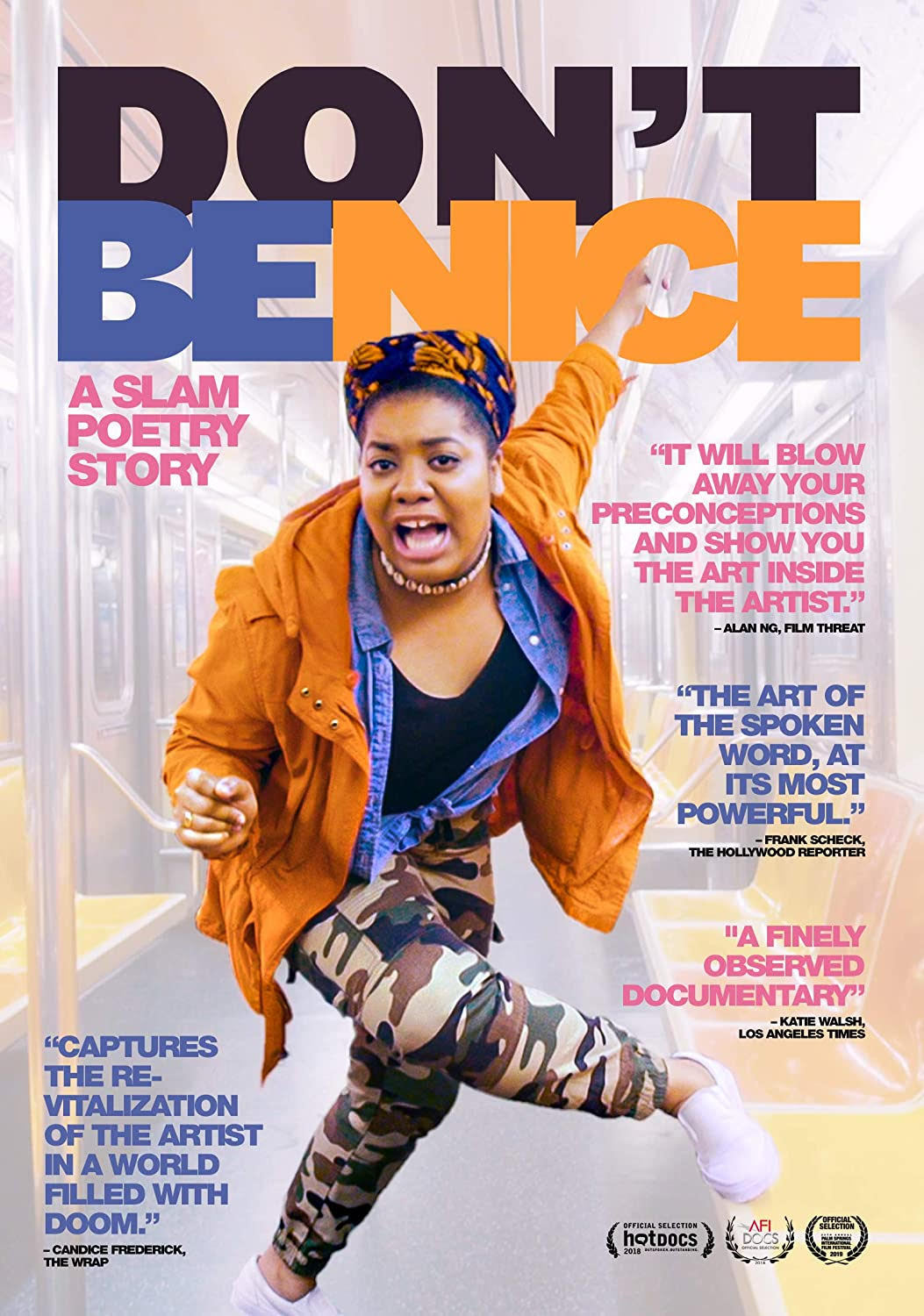

Nikhil Melnechuk has always been a storyteller, but his mind has always been in a more fictional world. So when he got the chance to produce a documentary about slam poets making their way in today’s world, it was a change of pace for the filmmaker. Yet, he nails the story of an NYC slam poetry team looking for a national championship with his documentary Don’t Be Nice.

An actor, poet, and filmmaker on top of producing, Melnechuk has spent his life trying to tell unique and interesting stories. He won over the festival crowd with his short films Jack and Jill and Something Happened, and he’s aiming to do it again thanks to his new documentary.

We spoke with Melnechuk about storytelling, filmmaking, and Don’t Be Nice.

Tell us about your filmmaking journey. What did you do before becoming a filmmaker?

I started young — before filmmaking… I did all of my homework. But seriously, once I got a video camera in my hand, I tried to turn every school assignment into a movie project. Even Latin essays became little films. Thankfully I had open-minded teachers who encouraged this. Though my Latin is a bit shaky.

What was the first project you worked on?

In middle school I made a short called Where Are All The Clowns? starring Azwan Badruzaman (who is now a writer/director/actor himself with a short film Reasons For Leaving currently on the festival circuit). It was a moody piece — shot in black and white, with no dialog — about a burglar who has a change of heart when he accidentally sets off a music box on an old lady’s dresser.

It won Chicago’s Compass Theater Teen Filmmaker award. Making it, there was no self-doubt among any of us. We just stepped to it.

Who are your current influences?

Josephine Decker (see Madeline’s Madeline), Raphael Bob-Waksberg and Kate Purdy (see Undone), and Nicole Jefferson Asher (see Self-Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker).

Do you consider yourself an indie filmmaker? If so, do you think you’ll ever stop being an indie filmmaker?

I suppose I’m an “indie filmmaker” until a studio picks up one of my projects. I’d like to be a “good filmmaker.” Jury’s still out on that one, but there are good filmmakers making zero budget films and country-sized budget films. What matters to me is that I find myself enough to discover what I want to say, and experiment enough to develop the skills to say it. This is what the poets did in Don’t Be Nice. I’m inspired by them.

Was there any movie you watched that inspired you to become a filmmaker?

John Landis’ The Blues Brothers, because it was so damn passionate.

Along with being a filmmaker, you’re also a poet. Why do you feel the two go together?

Practically, they’re opposites. Poetry is solo, free to write, and sits on the edge of the market. Film is collaborative, expensive to shoot, and is bought and sold. But they complement each other, too. Poetry puts someone else’s inner monologue inside your head, and film gets close to being a lived experience. They each provide a path to feeling.

Is there one genre of filmmaking you prefer over another?

I like dramas… because life isn’t sad and hard enough already. But really, I like dramas because life is sad and hard and catharsis is real. Hey, maybe I like dramas because I’m secretly a gossip and can you believe that happened to her and she did that to him and he did what now?

Walk us through your creative process.

When I’ve got a seed of an idea I pace back and forth 15th street between 8th avenue and the Hudson River talking ideas out loud. And get a coffee (decaf these days… I know) along the way. And then stay up late and bang it out on the computer. I often wake up in the middle of the night with a better idea.

Then in the morning, I share it with my girlfriend and partner Melissa Jackson, and she lets me know whether I should keep going or shove it.

What was your experience like on Don’t Be Nice?

All-consuming, wrenching, and celebratory. Good and bad and everything in between. The Summer of 2016 might have been the calm before the November election storm, but instead it was a storm of senseless violence and impassioned activism. We were a small team of filmmakers working beside a small team of poets.

The poets were trying to process the trauma around them and spit it back to the world as personal poems. And the filmmakers, we were trying to make art about their art about that trauma. This all meant that there was no creative separation for any of us, no way to “step back.”

Add to that, the two years of production and editing were based out of a basement “office” with no windows and no bathroom. And now, we’re releasing the film into a world that seems hell bent on repeating the mistakes of that summer, but also a world that is more awake to them. I hope I can give a better answer in another four years, right now I’m still in it.

What drew you to producing Don’t Be Nice?

I was running the Bowery Poetry Club and, hearing mind-blowing spoken word poetry on a daily basis, had one thought: more people needed to experience these poems and meet these poets. The club had a max capacity of 125. Not enough. We had to find a way to take the poetry to the people, and we had to find a way to help open those new to poetry to hearing it.

We thought about mounting a stage play, booking poets on college tours, even making an app for poetry videos. As a teen I’d worked for the maverick filmmaker Katy Chevigny (see Election Day, Deadline, E-TEAM) and learned from her that documentaries—especially those made with the realism and character focus of vérité—could be used as pillars of social movements.

The poets were writing about big, difficult, political issues from a personal perspective. What if we could make a film around their words that opened out into the larger world? This felt like the challenge of a lifetime.

Do you feel like Don’t Be Nice’s message is more relevant than ever? Why?

Oh yes absolutely, but I’m wary of telling audiences why because the message I take from it might not be the message they take from it. I don’t want to tell anyone what they’re supposed to think about what they see; I hope they’ll be intrigued enough to see it for themselves.

The film’s themes, however, are undeniably more relevant than ever. Don’t Be Nice questions the role and expectation of an artist in a time of social revolution, and looks at racial injustice and how it is maintained and how, perhaps, it might be overcome.

You’ve worn a lot of hats over the years. What is that like?

I’ve got serious hat hair. Actually, my head’s too large for most hats. But it’s an apt metaphor because you can only really wear one hat at a time. And if you usually wear the “producing hat” (which is probably more of a bald spot) and you walk in one day with the “acting hat” on, some people get very confused, or worse, they don’t take you seriously.

But maybe it’s more the other way around. It’s hard to take yourself seriously. Then again, Werner Herzog declared that filmmaking had made him into a clown.

Is there one part of filmmaking you prefer over another?

Orson Welles once said “… the whole eloquence of cinema is achieved in the editing room.” You’re taking these phrases of image and sound that are meaningless out of context and you’re trying to weave them into a story so they make enough sense to communicate something of beauty. It’s like you’re a baby again!

Do you prefer being in front of the camera or behind it?

I just like being around it. We each have our own perspective on life, and see the world from that perspective and only that perspective. The film camera is a shared perspective. It’s put down in a scene, or carried around a scene, and everyone on that set is focussed on what it is seeing. We all become facets of its one eye.

What has been your biggest success and failure so far?

I wanted to climb a coconut tree in Jamaica and bring down a coconut for Melissa. I tried and tried but couldn’t get more than a foot off the ground. I almost gave up, but gritted my teeth, forgot about the limitations of my body, and scurried twenty feet to the top. Success!

But once up there, I realized I didn’t know how to pluck the coconut, and I didn’t know how to get back down without cutting my bare limbs. Five minutes later I was standing at the base of the tree, every part of my body bleeding, and with no coconut. Apparently, there are better and worse ways of doing things, but as a friend once told me, you’re more likely to regret the things you didn’t do than the things you did.

Where do you see yourself in five years?

In good trouble.

Could we see any episodic TV from you in the near future?

From your lips to God’s ears!

If any director could direct the story of your life, who would you choose and why?

Terry Gilliam. He captures the absurdity of life without stripping it of its meaning.

If you could only watch one movie for the rest of your life, what would you choose and why?

Faces, by John Cassavetes. The light and dark of a couple’s present and future is squandered and redeemed in that film.

Do you have any experience with mentors? If so, would you recommend them for up and coming filmmakers?

I’ve sought out and found a mentor at a number of different stages of my life. There’s no substitute for experience, and that’s what a mentor—good or bad—will give you: an opportunity to watch and assist and learn.

However, if you want to be a filmmaker you can’t be an assistant forever, so you’ve got to be ready to make the jump from being a mentee to being a peer. Some mentors encourage this, and others don’t. I’ve had both kinds. Ultimately my mentors taught me to throw myself full force into any project — whether or not it’s “your own”— so that you make conscientiousness a habit.

What’s coming next for you?

I’m developing a fiction series about poets in New York, writing a feature about a woman bull rider, and directing an improvised feature about a pair of artists battling over the right way to deal with their past.

Are there any indie artists we should be keeping on our radar?

Look out for writer/director Randall Dottin. He’s a natural storyteller — he knows how to build a plot around the beating heart of an idea, and shape characters who would be most challenged confronting that idea. I had the pleasure of working with him on his latest short FEVAH, starring Melissa Jackson, Russell Hornsby, and LaRoyce Hawkins.

Randall’s now working on developing “The House I Never Knew,” a six-part documentary series that will chronicle the lives of people struggling to fight against the negative effects of housing segregation policy in Wilmington, NC, Houston, TX and Boston, MA.