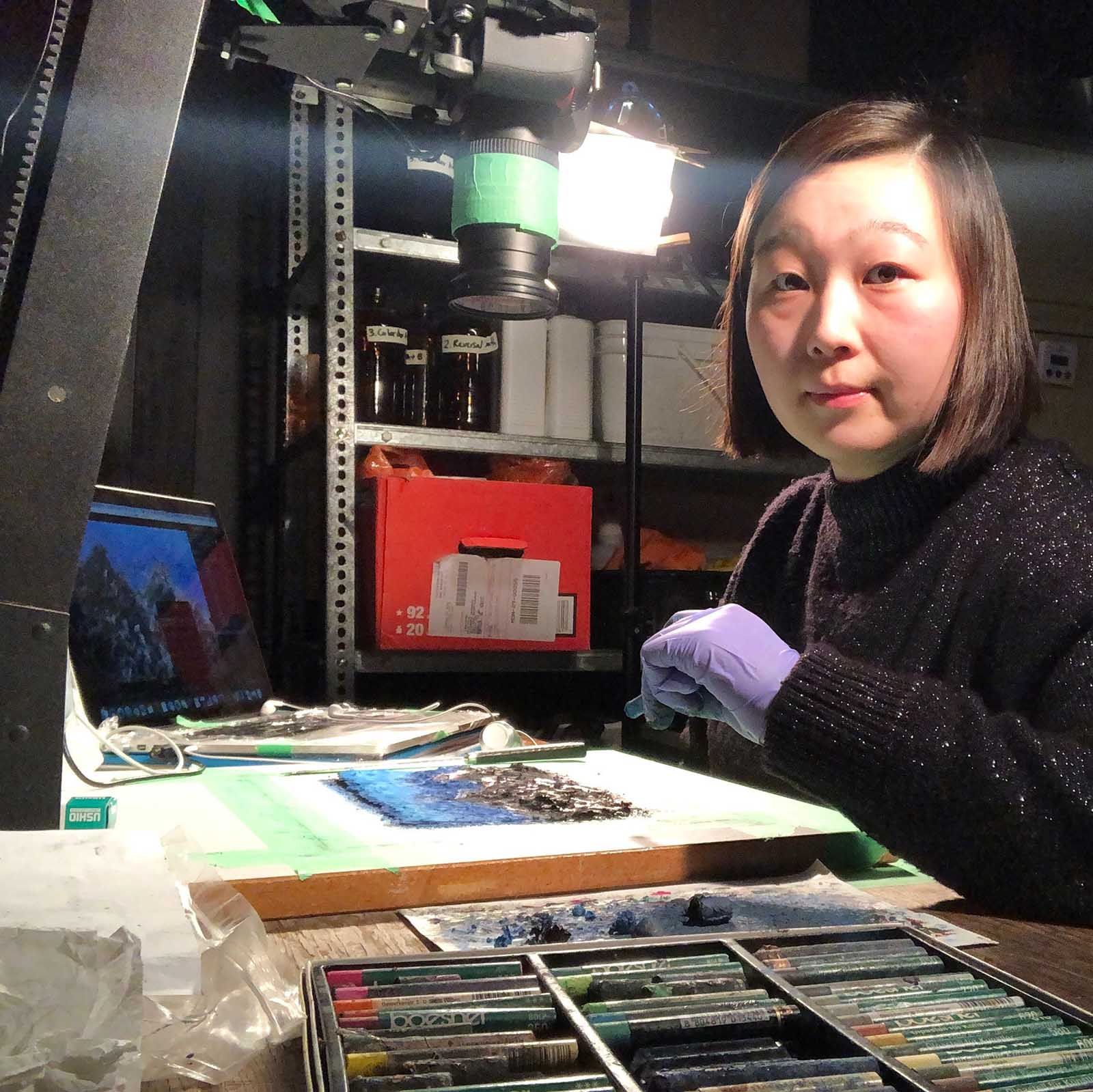

Hear from visionary director Alisi Telengut on her short film ‘The Fourfold’

Tradition is only as effective as the methods of passing them down. If a culture is never documented, how is anyone meant to remember its existence centuries later? The Fourfold is the perfect example of preserving tradition for the next generation. The short film tells the story of animistic beliefs of the Mongols & Siberians.

What makes this short film stand out from other animated films is because director Alisi Telengut paints each shot of the film live as she’s filming. All the visuals you see in The Fourfold are created by Telengut, and painted over to make way for the next shot. It’s innovation like this that makes Telengut’s work above and beyond.

We spoke with Alisi about The Fourfold and her creative process when painting.

Tell us about your journey into the arts. What did you do before becoming an artist or filmmaker?

I have been interested in painting since I was young, but I went to a film school by chance and started my formal education in film animation. As a student, I saw many independent animated films and auteur films that encouraged me to continue my own practice.

Is there any particular film or TV show that pulled you towards filmmaking?

I was very inspired by the work of the South African artist William Kentridge and the short films by the Russian animation filmmaker Yuri Norstein. Both of their works were done under the camera but with different techniques and workflows.

What made you decide canvas painting was the perfect technique for telling your stories?

The visual is not necessarily created on canvas, but on any flat material, such as a single piece of paper. By animating (mostly) on a single surface, it’s an accumulative and straight-ahead process. I think it represents one of the most direct sense of the creator’s mind with the hands-on practice and physical materials.

Walk us through your creative process.

I worked with the under camera workflow, it is a way of time lapse photography of painting. The process is to animate on the same artwork over time which is very different from ‘clean-looking’ traditional animation on many papers or digital animation on computers. The birth of every frame is to erase the older one, leaving some traces of previous frames behind.

The painting/animation is fixed at the same place and a fixed camera takes pictures of the artwork. When the pictures are played back continuously, they become alive. So the film was created straight-ahead frame by frame by hand on a single surface, including the transitions and morphs between scenes.

This technique allows for many possibilities and room for improvisation. However, if a mistake is made, it is very difficult to correct it because it is built on top of the previous frames.

Do you think live art on film is a more effective storytelling method than still life paintings?

I think film has a great combinations of using image, sound, music and various elements to convey ideas.

What was the first film project you worked on? What did you learn from the experience?

My first film project was a collaborative short film that was shot on a Bolex camera with the pixellation technique. We staged and animated ourselves frame by frame, against animated graffiti backgrounds in an abandoned industrial area in Montreal. It was the first time that I understood stop motion in a much clearer way.

What inspired you to create The Fourfold?

It is based on the animistic beliefs and shamanic rituals from Mongolia and Siberia. When I was a child, I heard about the rituals from my grandparents who used to live as nomads on the Mongolian grassland. After I grew up, I learned that these beliefs and rituals are called animism, which is a term from a British anthropologist in the 19th century.

It described that Western European have advanced to the highest stage of science, while the rest of world’s people were still “primitive” and animistic. Of course, this out-dated colonialist notion was long shunned. The animistic idea is that trees, rivers or the entire cosmos are considered as alive, are treated as a person rather than as an object.

In the past twenty years, the idea of animism has been reconsidered and has become self-description among indigenous populations for land rights, the protection of natural resources and environmental ethics.

What was it like creating The Fourfold live as you were filming?

The process was a bit repetitive, but I was excited to animate some plants.

You were the definition of a one-woman show while creating The Fourfold. How do you juggle all those responsibilities?’

I wish I had a bit more time to work on this film as a one-person team. I went through all the creative processes, from the storyboarding, sound design, till the final export of the film. But I’m grateful that the sound mix was supported by the award winning sound designer Olivier Calvert.

What do you hope people take away from watching The Fourfold?

There are other ways of how humans relate to nature outside of the Eurocentric point of view since the time of modernity and colonialism. In many indigenous cultures around the world, nature is not considered as a static “environment” nor a Galilean object to be exploited, instead, is considered as alive, is worshipped as a deity/deities and celebrated as home.

You choose to destroy your art after creating it for the films. Why do you choose to do that?

Because of the particular animation workflow, every new frame is created on top of the previous frame. There’s a forward momentum to it, so the only art that is left at the end is the last frame of the film.

How did you decide what specific parts of Tengrism to feature in The Fourfold?

Tengrism is a shamanic tradition and belief for Mongolic and Turkic peoples since the ancient time. My film is based on the voice interview of my grandmother who used to live as a nomad on the Mongolian grassland. In the film, she talked about Ovoo worshipping, milk libation, and Fire God worshipping rituals associated with Tengrism.

Ovoo is shamanic stone altars built for praising the sky deity Tengri, Mother Earth, peace and harmony. Milk libation ceremony usually takes place on the summer solstice by sprinkling milk into the air to praise nature spirits and ancestors, while Fire God worshipping ceremony happens on December 23 in the lunar calendar.

Do you think it’s important for filmmakers to use their platform to send messages to their audiences?

Yes, I think so. Films of course create messages, but social platforms help create more dialogues and interactions.

Where do you see yourself in five years?

I want to write and publish a book on my research, finish a few short films, and create a large-scale installation.

Would you ever consider doing an animated film using a different technique?

Yes! I made a short stop motion film titled La grogne coming soon this year. The film was created with a mixture of stop motion puppets and under camera painting. The puppets have movable metal armatures inside, covered with felt.

How do you think other filmmakers can work towards preserving the Earth?

First of all, I think the anthropocentric point of view towards Earth has to be challenged and shifted. I’m glad that there are already many inspiring books, films and art focusing on this topic in recent years.

If any director could direct the story of your life, who would you choose and why?

Sorry! I’m not sure I would want to see that happen.

If you could choose any painter to paint your self-portrait, who would you choose and why?

I would be curious to see an Artificial Intelligence art. AI is of course one of several technologies that will have an impact on the art in the future.

What’s next on the docket for you?

I’m excited to share the stop motion puppet film La grogne soon. Meanwhile, I’m working on a new project that explores the sympoietic relationship of man and non-human, based on the mythologies of the indigenous Buryat people around the Lake Baikal in Siberia.

How has COVID affected your projects?

The post-production of the stop motion film has been delayed for several months, but we finally managed to finish the project. I had also planned to conduct a field research and interviews in Siberia in summer 2020 for my new film, but I can’t travel in the foreseeable future and I would have to find an alternative way to do research.

Do you think the film industry can recover completely once COVID dies down?

It’s possible that many festival and industry events will stay online in the future even after the pandemic. Because they’ve already invested so much resources to build online platforms.

What advice do you give up and coming filmmakers looking to make their mark on the industry?

Keep experimenting and keep carrying on.