How the computer screen became a cinematic canvas

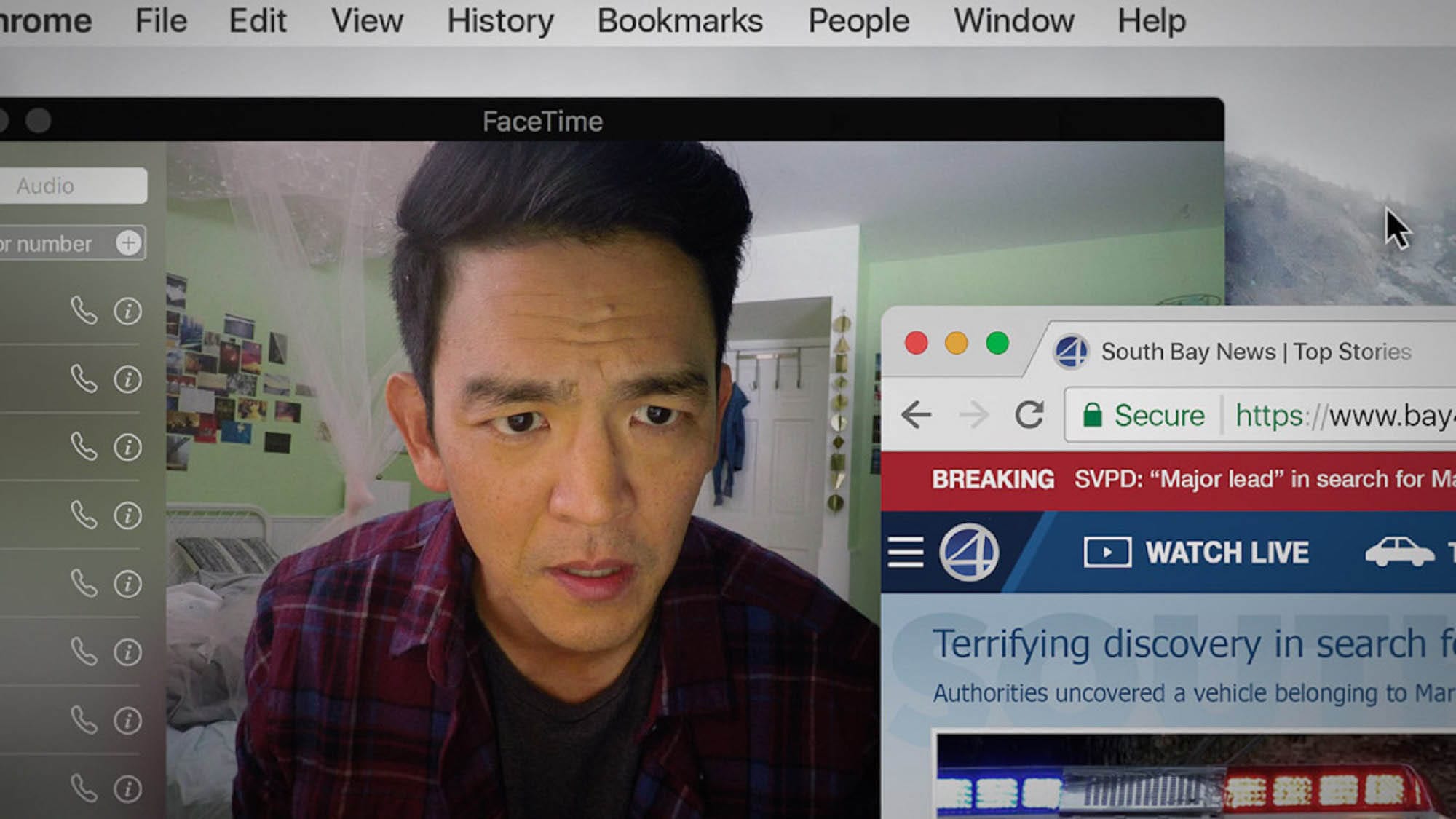

Following a father who breaks into his daughter’s laptop in order to find clues pertaining to her sudden disappearance, Aneesh Chaganty’s Search utilizes the computer screen as its primary storytelling tool. Revealing the real-time mounting panic of someone desperately digging through a computer for clues, Search reinvents a common crime investigation with a modern yet bracingly familiar narrative device.

Following the movie’s world premiere at Sundance, The Hollywood Reporter mused upon the all-too-familiar “web voyage of disturbing discovery” the movie presents and acknowledged how “practically everyone knows what it’s like to go down the rabbit hole of the internet.” In doing so, Search treads familiar ground to a number of films in recent years that have strived to represent the ubiquitous ways we use technology as a way to tell an otherwise common story.

Several reviews of Search expressed the opinion that using a computer screen as a primary cinematic storytelling device is a “gimmicky” premise – albeit one that “reaches way beyond that . . . to deliver an engrossing ride” as IndieWire put it. However, it may be disingenuous to suggest such a device should be highlighted for its artifice – particularly taking into account other projects’ effectiveness in relying on a computer screen to tell a story.

Like Search, crime thriller Open Windows brings audiences into the fold of real-time online communication to allow us a view into the abuse of technology and character reactions in tandem. Likewise, horror movies like The Den and Unfriended made viewers uncomfortable witnesses to hideous crimes as they played out in online forums. Adding to the unease of such movies is the conceit that their screen is also our screen; we share in the horror of their lead characters in real time.

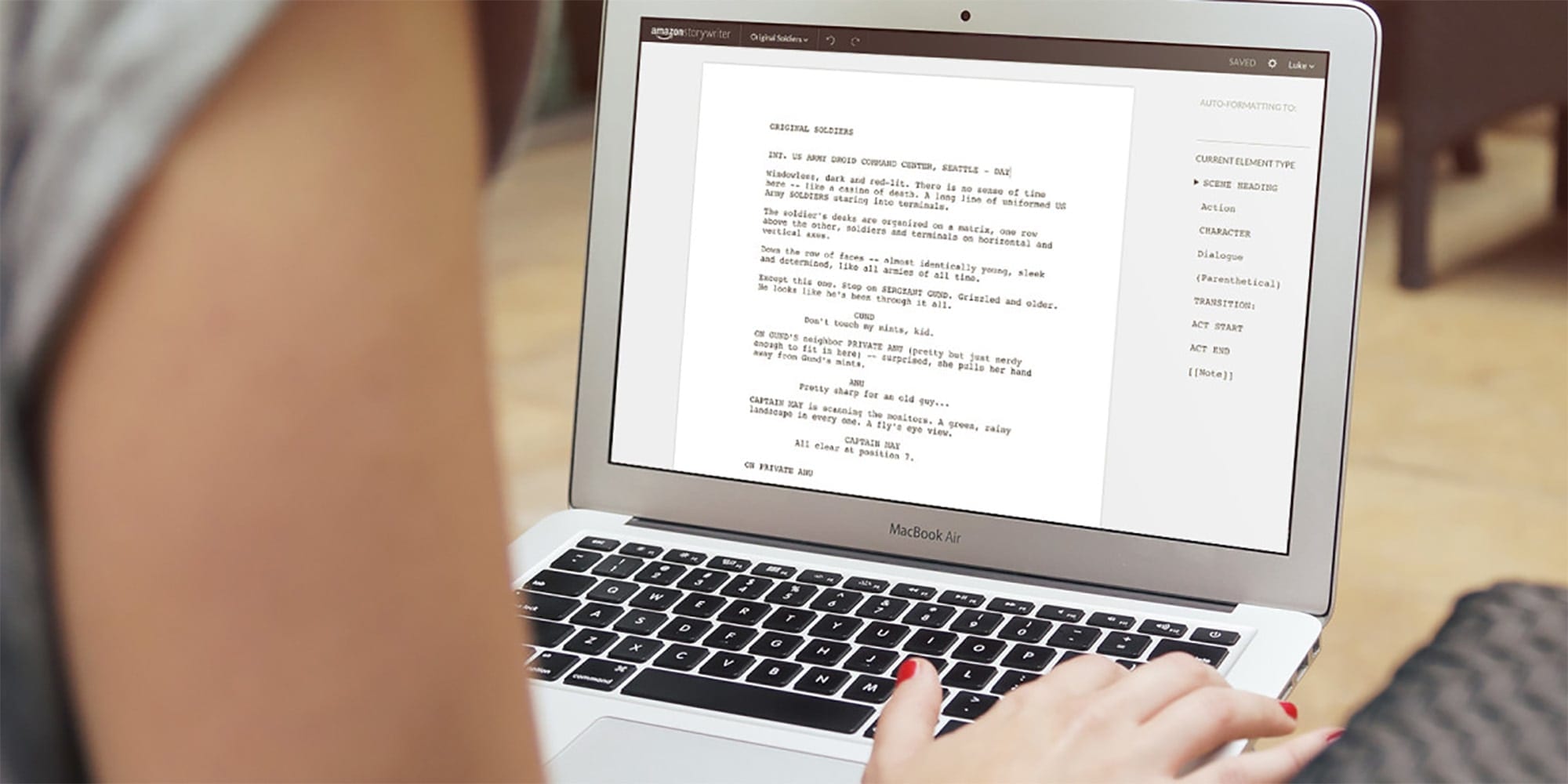

As content becomes more driven to online streaming, a natively digital form of storytelling feels all the more imperative. Watching such a story played out on your own laptop can be chillingly tangible, a cinematic landscape accessible to nearly every viewer who encounters it and therefore all the more unnerving.

This landscape also lends itself to the everyday online and technological habits in which we regularly engage. As THR also noted in their Search review, “David (John Cho) spends a great deal of his time online, and there is a certain comfort in this: don’t we all? The familiarity of most of the places David inhabits online invites dramatic complicity.”

Moving forward, it’s easy to fathom how direct reflections of computing experience could become more regularly integrated into film – particularly as audiences may opt to watch movies online rather than in theaters. As a 2014 video from Every Frame A Painting suggested, use of the computer screen as a movie canvas could become a “convention” rather than the sort of gimmick reviews of Search write it off as.

In doing so, movies would move toward a more realistic portrayal of the ubiquity of digital communication and technology in our day-to-day lives in a way that could genuinely resonate with today’s audiences.

Rather than positioning viewers as outsiders merely observing a character interacting with a screen, movies like Search are instead inviting us to be engaged witnesses to characters’ interior digital lives. And by drawing us into the emotions that dictate digital activity, we can be pulled closer to the intimate details of a character while observing our own digital habits in the process.

We live so much of our lives in front of screens, communicating digitally rather than in person, “IRL”. Reflecting that truism in filmic storytelling isn’t so much a gimmick as an astute portrayal of our everyday lives, as much offering a sense of comforting familiarity to the viewer as unfurling uncomfortable truths.

Either way, integration of the personal digital experience into film has much more to offer – whether out of pretentiousness or necessity, it’s a convention that could become far more commonplace than many are currently willing to admit.